The Fed should target the forecast

Inflation doomsayers are almost certainly wrong, but a 75 BP hike is still a good idea

April 11’s inflation print came in at 1.2% month-over-month, the highest monthly rate since 2005 and the highest year-over-year rate since 1981. The persistence of this inflation has thoroughly discredited so-called “Team Transitory”, the network of left and center-left economists who insisted last summer and autumn that elevated inflation levels would soon subside as the remnants of fiscal stimulus tapered down and supply constraints eased. Inflation hawks and armchair central bankers have taken this turn of events to mean that the Fed needs to drastically raise rates. But perhaps the pendulum has swung too far against the Fed. While the monetary authority deserves much of the criticism they have received, I think market indicators suggest their performance might be under-rated. Some small changes – starting with a modestly accelerated rate hike schedule – could be the cherry on top of what has been a herculean anti-Covid effort .

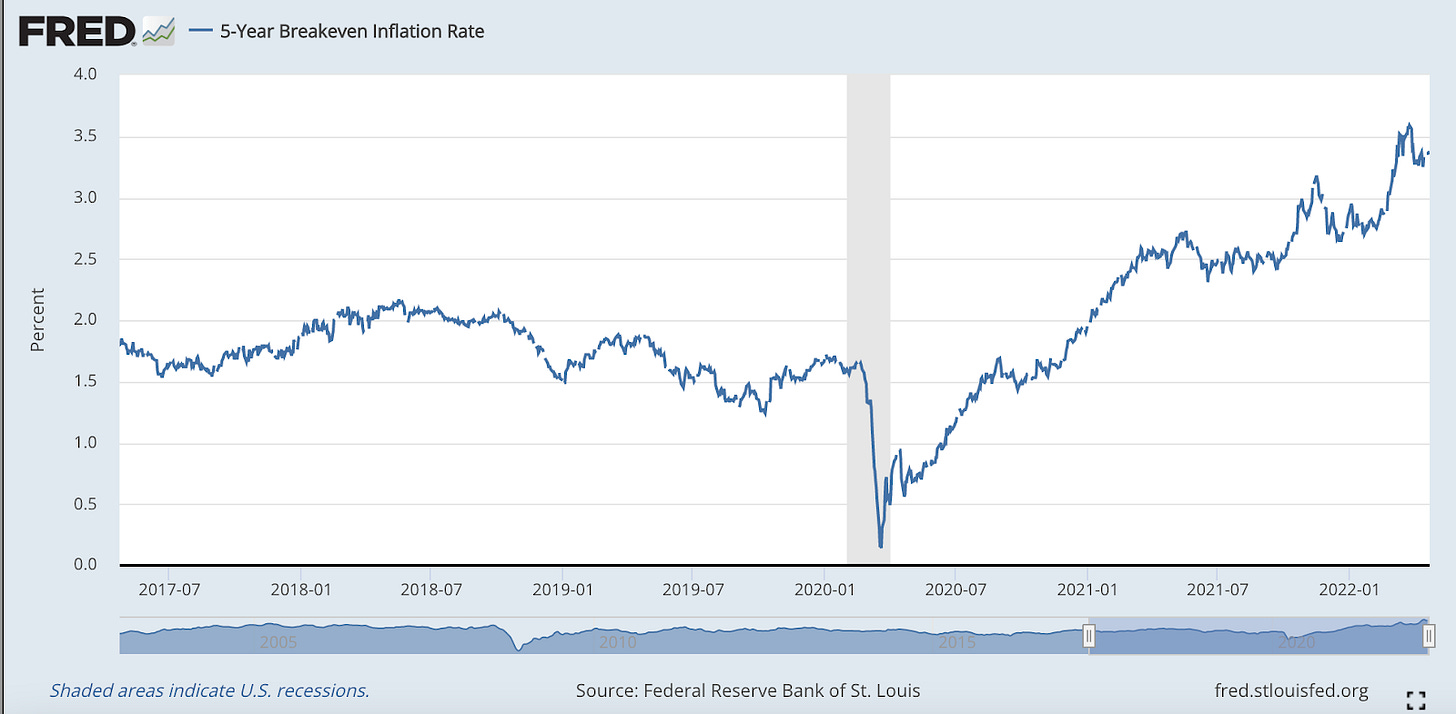

I’m a market monetarist, which (very) roughly means that I believe that market indicators are useful metrics for forecasting important macroeconomic indicators. For instance, consider the TIPS spread, which is the difference in yield between inflation-protected Treasury securities and standard unprotected Treasury securities. That difference should (roughly) map to expected inflation. If the market “actually” expected 5% inflation, but the spread was only 3%, then a savvy trader would enter the market and eat the expected 2% gain. You don’t have to be an Efficient Markets Hypothesis fanatic to believe that highly liquid markets should be more accurate than any one pundit or economist – one party has a much larger stake in being right than the other.

So what are these indicators actually saying? The five-year breakeven inflation rate (which represents the difference between 5-year inflation-protected Treasuries and 5-year unprotected Treasuries) is 3.37%. If we expect 2022 to have 5% rest-of-year inflation, that maps to an average of less than 3% yearly inflation for the following four years. The five-year, five-year forward inflation expectation rate – which uses the TIPS spread to measure expected inflation 6-10 years from now – currently sits at a pretty 2.59%. This isn’t exactly the 2% the Fed is supposed to be targeting on average, but I have yet to see quality research that says that there’s meaningful harm to having a stable 2.5-3% inflation rate. These aren’t cherry-picked numbers – these are the two principal market-measures of inflation. These are the best measures that we have, and they indicate that today’s elevated inflation will come down.

We’re already seeing the early signs! Despite high headline numbers, core inflation – which strips out the volatile and un-predictive fuel and food price changes – was just 0.3% in March. If we look at one-year inflation markets, their expectation of 6% inflation in 2022 suggests roughly 4-4.5% inflation from April-December (since there has already been so much from January-March). With inflation likely still elevated in April and May, that suggests that end-of-year inflation could genuinely be back to a stable 3% annualized rate by December.

The Fed deserves a fair amount of praise for the way it handled the COVID-19 pandemic. Navigating a 9% drop in GDP without a financial crisis is insanely difficult. And it took less than two years to cut the unemployment rate from 14.7% to below 4%. It took almost eight years to achieve the same feat in the aftermath of the Great Recession. When there is a severe supply shock–like COVID-19–you can either cover the gap through mass layoffs or through inflation, there’s no middle ground. The Fed clearly made the right choice here.

But they started erring around last autumn. Probably the best forward indicator of inflation outside of TIPS spread is nominal GDP (NGDP) expectations. Nominal GDP is just the total spending in the economy, which equals real economic growth plus inflation. While the Fed has only limited control over real variables (especially in the medium-term), they have almost complete control over nominal variables. After all, nominal GDP is just the money supply, which the Fed controls, multiplied by the velocity of money, which shouldn’t vary too much outside of extreme shocks. By Q4 2021, NGDP was fully back “on trend” with reasonable expectations showing a major overshoot for 2022. The official report for 2022 Q1 won’t be released until Thursday, but an overshoot of $200 billion - $400 billion seems likely (sadly, there are no liquid NGDP futures markets to get a more precise number from).

Why is stable NGDP growth such a good target for the Fed? Because it’s the best way to mediate between conflicting demands for high employment and low inflation. Suppose there’s an adverse demand shock, such as in 2008, and real GDP falls. If the Fed keeps total spending in the economy (NGDP) growing at a constant rate, then there’s just as much money to keep paying the same workers as before. While that will inevitably generate inflation–since the only way to offset the drop in real GDP is with inflation while keeping total spending growth consistent – that’s totally worthwhile during a recession to keep unemployment low. But if NGDP is above - trend as in the 1970s and today, that suggests that the Fed is generating inflation without getting commensurate employment benefits.

The challenge is getting NGDP back down to trend without causing a recession. Goldman Sachs estimated two-year recession risk to be 38%, while Deutsche Bank now considers a recession by 2023 likely. The severity of the recession matters a lot here – there’s a big difference between the 1980s Volcker recession where unemployment topped 10% and the more mild one of the early 1990s–but this was pretty avoidable if the Fed had used available market-based estimates.

But perhaps the biggest issue is the threat to Federal Reserve credibility. In 2020, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced a much-needed “flexible average inflation target”. Previously, the Federal Reserve would target a 2% annual inflation rate each year. If they undershoot and hit only 1% in one year, they’ll still aim for 2% the year after. Under the new FAIT regime, they’d respond to that 1% year with a 3% rate the following year. By responding to undershoots with overshoots (and vice versa), the new regime provides far more long-term price stability than the old regime.

The problem is that they totally failed to follow through with this target. To meet an average of 2%, you’d need to respond to an 8.5% year with four years of near-zero inflation, which would probably require a sustained recession to achieve. As evidenced by the market estimates of 3% and 2.5% medium and long-term inflation, no one seems to believe that the Federal Reserve will even try to hit their stated target.

Now perhaps this isn’t so bad. If the stated regime would require extreme pain to accomplish, perhaps we should abandon it. As the saying goes, a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds. But inflation is expectations-driven. If people expect inflation to persist, then they’ll preemptively raise prices, further accelerating inflation. In contrast, if the Fed credibly promises to do “whatever it takes” to stop inflation–including extremely painful actions–people will avoid those price hikes, thus potentially stopping inflation without actually having to take those steps. If the Fed is abandoning policy regimes left and right, I worry about their long-run ability to stave off inflation without actually having to back up their tough talk [full disclosure: I worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in 2020 and 2021, but I was not involved in these matters and I have no insider information into their thinking].

The Bottom Line

So how does this impact the upcoming May FOMC meeting? I think I might agree with economist Scott Sumner here. I don’t have a great mental model of the mechanical effects of what a 50 BP hike does to inflation versus a 75 BP hike. But if the market is pricing in a 50 BP hike in May and pricing in inflation to be above target for the medium-term, then the Fed should hike more than the market expects. They should adopt whatever policy results in the market expecting NGDP to remain on-trend. And the current policy is failing to do that.

Ultimately, the backseat economists among the Twitterati warning about hyper-inflation are all-but-certain going to be wrong. The Fed (for the most part) has this under control. The eye-popping price hikes of the last year are going to continue to slow down and will do so rapidly. But there’s room on the margin for improvement, and that starts with slightly accelerating the pace of rate hikes.